THE HYLAEUS PROJECT

A CREATIVE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ENDANGERED NATIVE HAWAIIAN HYLAEUS BEES

{WITH AIDAN KOCH}

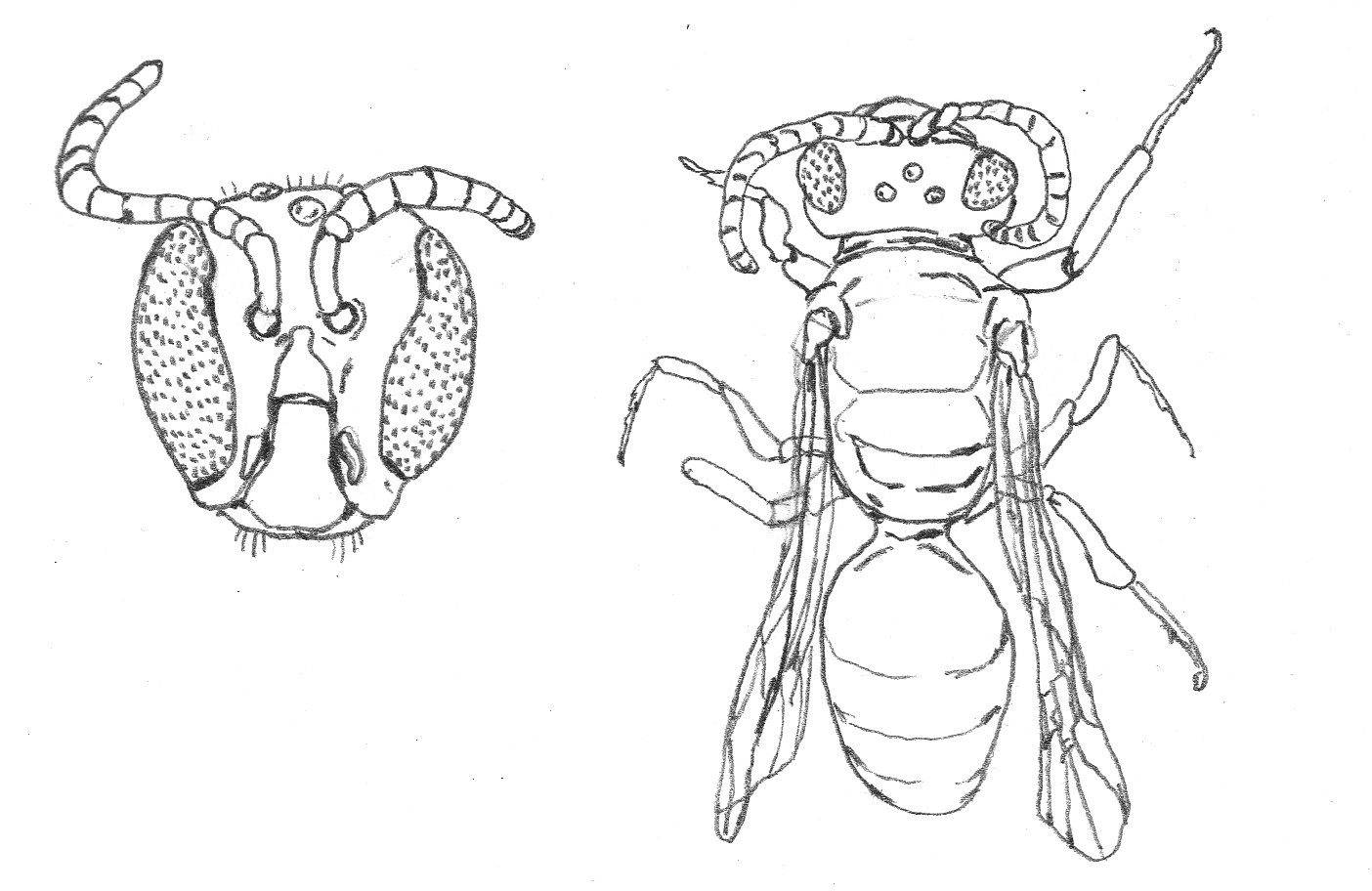

In 2008 while working for the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation I co-authored petitions to the US Fish & Wildlife Service to list seven Hawaiian Hylaeus species as endangered. These largely overlooked bees are vital pollinators of native Hawaiian plants, and they had been vanishing without hardly any notice. A few years later, I took the information I had learned and began The Hylaeus Project - an experiment in using art to get the word out about these imperiled and fantastic species. In the summer of 2013 artist Aidan Koch and I spent a month in Hawaii documenting the Hawaiian Hylaeus through visual art, natural history writing, music composition, and photography. We traversed all sorts of present and former Hylaeus habitat to find them, from beaches to barren lava flows and montane forests, with our nets, aspirators, notebooks and recording devices in tow. {The Hylaeus are commonly known as ‘yellow-faced bees’ for the pale ivory to bright yellow markings on the males’ heads.}

I compiled and edited our work into an illustrated book called The Hylaeus Project (designed and published by Publication Studio), and wrote a set of music compositions for Secret Drum Band. The book includes interviews with Hawaiian naturalists, watercolor plates and chapters on each field site that we visited. The music draws on the soundscapes of our field sites, and was featured in a 2014 cassette release and Secret Drum Band’s 2017 full length record, Dynamics.

On October 31, 2016, the seven petitioned species of Hawaiian Hylaeus bees were listed as endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Hylaeus anthracinus, H. longiceps, H. hilaris, H. facilis, H. mana, H. assimulans and H. kuakea became the first bees ever to be given this level of protection by the United States federal government. This status has been continually threatened by Republican representatives in Congress and the president, who see environmental regulation as an obstacle to economic development and have no regard for impacts to species, habitats, and communities. If you want to help to protect the ESA, please talk to friends and neighbors about how important it is, and make donations to groups such as the NRDC and the Center for Biological Diversity, who are working to protect this legislation. There are currently some wonderful projects going on in Hawaii to learn more about these bees and get the public involved in their protection. The Pollinators in Paradise program seeks to spread awareness of the endangered native pollinator and enlist the help of the Hawaiian community and visitors to Hawaii in conservation efforts.

The Hylaeus Project was made possible by a Project Grant from RACC.

The Hylaeus Project book & cassette are available for purchase in the shop!

In 2014, I returned to present the finished book and music in Hawaii. I made presentations at the Hawaii Conservation Alliance conference,

the Waimea botanical gardens, the Volcano Art Center, and Puuhonua O Honaunau (Place of Refuge). In 2016 I returned with an updated second edition of the book after the bees were listed, and made a presentation in Volcanoes National Park. This work has also been presented on tours in performances and lectures throughout the US and in Brazil. The Hylaeus Project has been featured in American Way magazine, the Oregonian, on the front covers of the West Hawaii Times in and 2017 and 2014 and in the Hawaii Tribune Herald.

<< JOURNAL ENTRIES FROM THE FIELD >>

In search of Hylaeus (8 june 2013)

Aidan and I have started our Hawaiian adventures – we will be in search of the native (and increasingly rare) Hylaeus bees on the islands of Oahu, Kauai and the Big Island for the next month. Several years ago while working at the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation I co-authoredpetitions to list several Hylaeus species as endangered. These species are now on the federal government’s candidate list for protection under the Endangered Species Act (which means a whole lot of nothing – but hopefully they’ll be listed in the next round of consideration for Pacific island species). Since leaving that job I’ve had it on my mind to return to the Hylaeus and to document these ofetn overlooked insects. I was awarded a project grant from the Regional Arts and Culture Council and this project has become a reality! Aidan and I spent a month in the summer of 2013 traveling through the Hawaiian Islands documenting the bees and their habitats. Aidan is a wonderful illustrator and drew and painted on our search; I made field recordings & composed percussion music inspired the soundscapes and character of our field sites. We kept thorough journals of what we come across, and our work has been compiled in a book called The Hylaeus Project. We’re sharing copies of the book and audio with scientists, educators, and anyone else who might take interest in the plight of these bees.

We spent an afternoon at the University of Hawaii – Manoa Insect Museum checking out specimens ofHylaeus, some collected a hundred years ago by R.C.L. Perkins. The following day we headed to the north shore and botanist David Orr showed us around the native plant gardens. The petals in the photo above are from a spectacular introduced vine that was growing in the gardens. We searched forHylaeus, but only found Ceratina spp., an introduced genus of bees that closely resemble the nativeHylaeus.

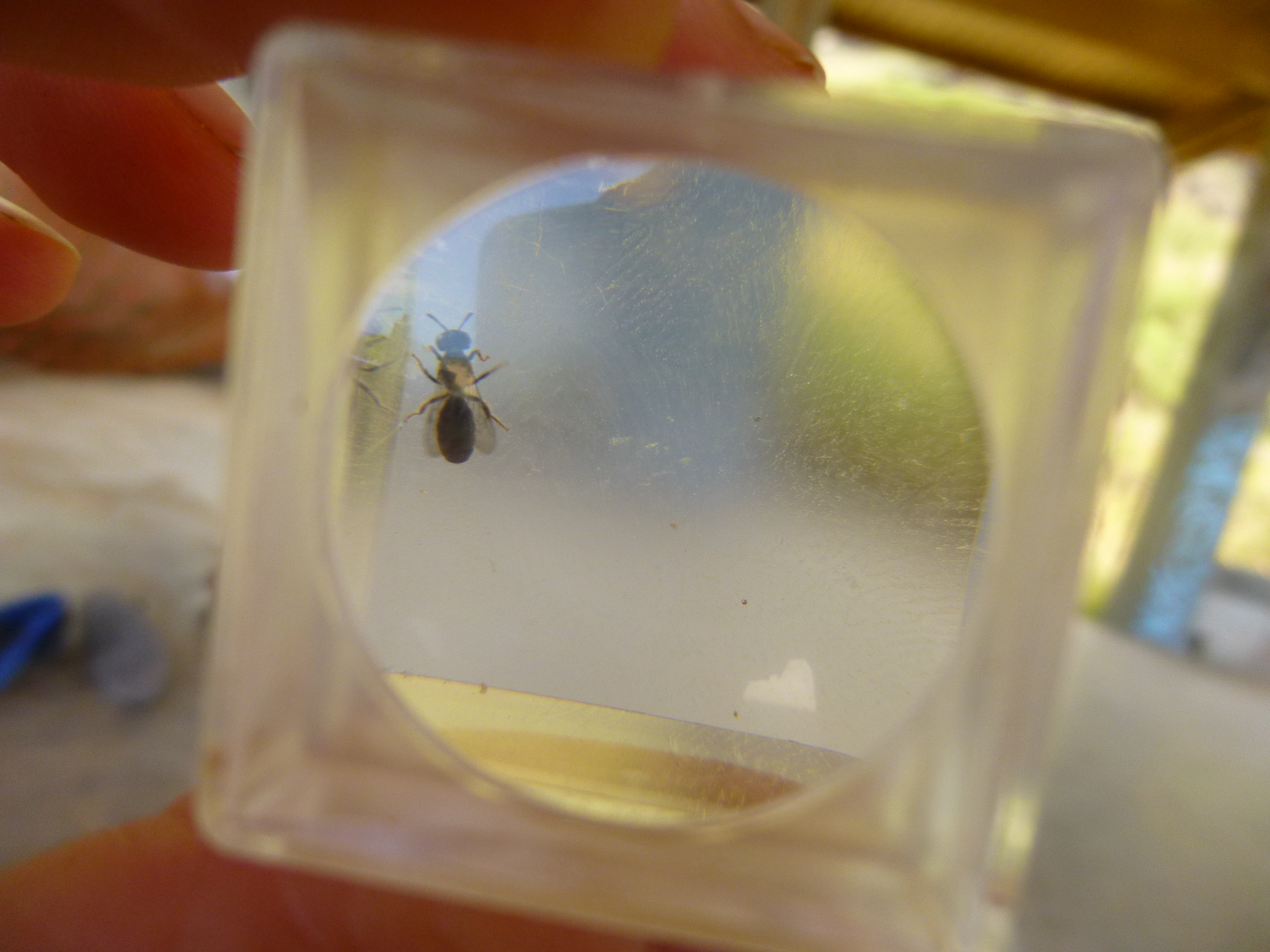

I have taken on a new sleep schedule – we go to bed by 11pm and wake up by 7 am. I love it! Aidan and I played an early show in downtown Honolulu a couple of nights ago at Manifest – it went really well – and got up early the next morning to join entomologist Karl Magnacca on a full day of hiking. I have been in touch with Karl over email for over 6 years; we first got in touch when we co-authored petitions to list several species of Hylaeus as endangered. It was so great to finally meet! We hiked up towards the peak of Lanihuli (in the Koolau range) until we reached the native vegetation. We were surrounded by species of Ohia, native ferns, koa, and a magical mist. The mist kept the Hylaeus from coming out, but we were treated to our first encounter with them later in the day at Ka’iwi and Sandy Beach, just east of Diamondhead. Hylaeus anthracinus was out and about, visiting flowers and nesting in coral & lava rocks. We’re headed to the north shore today to stay with some new friends on an estate near the ocean…..more soon!!

Oahʻu >> Kauaʻi (13 june 2013)

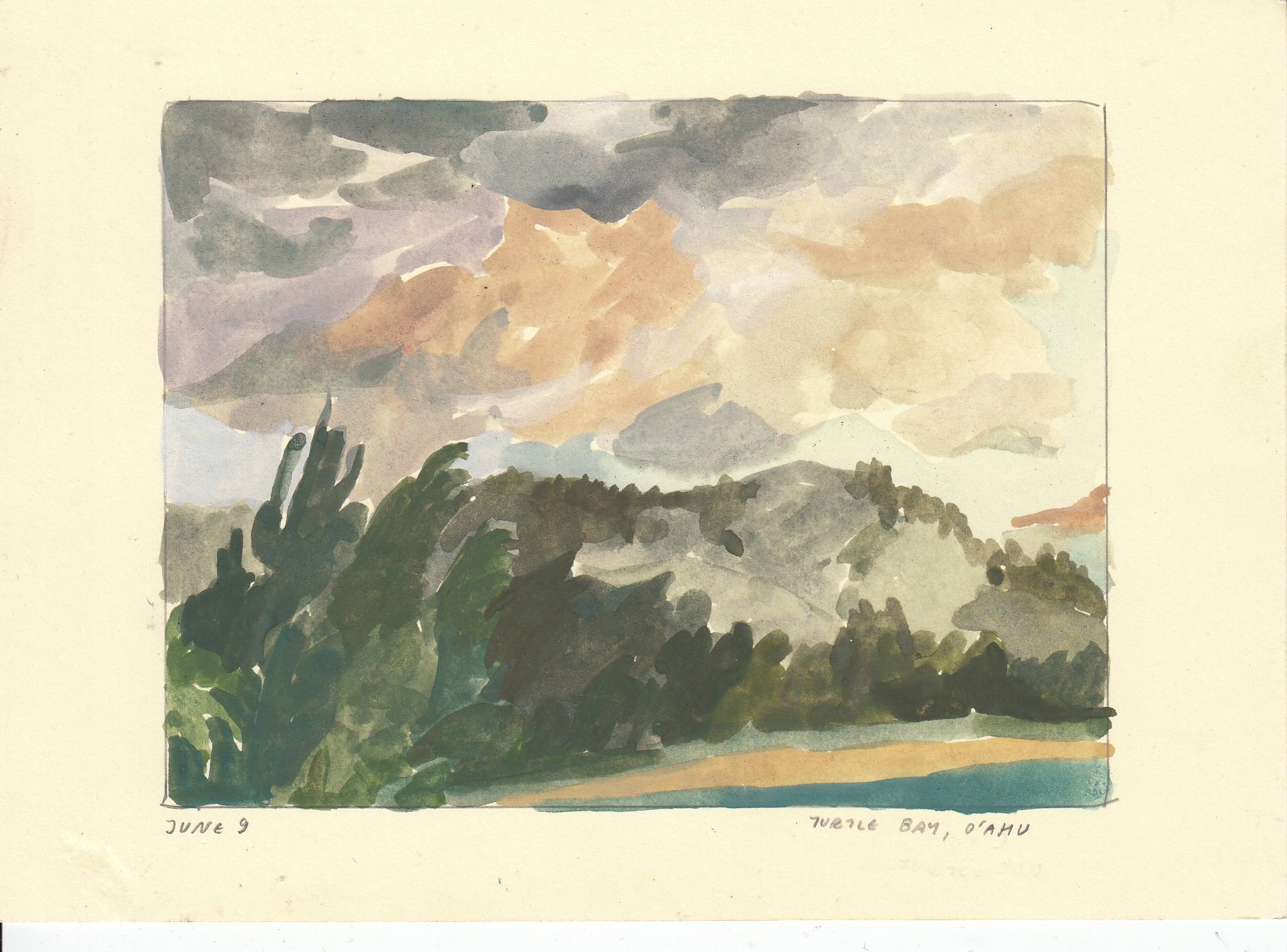

We spent three days this week on the north shore of Oahu and stayed with our new friends Aaron, Casey and their story-telling daughter Helix on the estate that they caretake for. We spent our daytime hours among the naupaka & heliotrope at the beach out at Kahuku Point nearby the Turtle Bay resort. This area is one of the few remaining habitats on Oahu where Hylaeus can still be found; they used to be abundant at Kaena Point, in northwest Oahu, but they’ve had a sharp decline there. Some people we talked to theorized that pesticide drift from nearby GMO fields may have impacted the bees.

The Hylaeus at Kahuku were far outnumbered by honeybees, large carpenter bees in the genusXylocopa, and other introduced bees. But they keep on hangin on! On one of our hikes back Aidan spotted two Hawaiian monk seals relaxing on the beach. These adorable and endangered mammals were resting about 50 feet from some men golfing on a world-class golf course. We noticed a sign asking visitors to keep a distance from any seals, and phoned in our sighting to the NOAA. What we really wanted to do, though, was cuddle with them.

Note: resort lobbies are great places to wrap up your work at the end of your sandy sweaty field days; some resorts have awesome karaoke nights.

We drove back to the city & hung out with our buddy Steve Gevurtz & his wonderful neighbors in their Honolulu compound of sorts. The next morning we flew to Kauai — we’re now staying with my old friend Ashley and her awesome kid Nico. We’ve spent a lot of time reminiscing about the beloved Sicilian restaurant we worked in together, Trinacria. Ashley has told us a lot about the GMO controversies on the island; so much land is being used for experimentation with some seriously risky & threatening new creations.

We visited the Kilauea Point Lighthouse/National Wildlife Refuge today. The little lighthouse has the most gorgeous contraption that projects the light (a complex prism called a fresnal lens). The area is populated by several kinds of seabirds that nest in the pali (cliffs) — albatross, frigate birds, red & blue-tailed tropicbirds, and wedge-tailed shearwaters. Ashley tells us that this site is the largest nesting site for seabirds in the main Hawaiian Islands. The recording below isof some of those birds — mostly tropicbirds, I suspect. The Hylaeus were thriving at this heavily-visited tourist site. They were loving the akoko, ilima, and naupaka growing all over the place. And we saw an endangered nene goose hanging out on the lawn beside the lighthouse. We ended the day with a swim at Hanalei Bay, with the misty mountains across from us. NBD.

Kauaʻi >> Big Island (26 june 2013)

Aloha! We are taking a day off in the city of Hilo, on the (relatively) rainy side of the Big Island (Hawaii Island). We hit up my favorite farmer’s market in the world — the Hilo Market, and are cozied up at Bear’s Coffeeshop catching up on some work in the shade. We’ve been staying in a cabin behind a friend’s house down a dirt road south of Hilo, and I have been loving going to sleep surrounded by lush green vegetation, and waking up to a cold shower in the morning. We fall asleep to a thick chorus of coqui frogs every night; the coqui are invasive here, and occur at much higher densities than they do in their native Puerto Rico. If I stop thinking about the ecological impacts of these lil creatures, I am able to enjoy their contribution to the soundscape — only if I also stop myself from wondering about all the other sounds they’re obscuring. I guess its some sort of meditation practice on being present with whatever assemblage of species are here in the moment, eh? Good thing Aidan is along on this trip; she has an unending fascination and appreciation for the geckos, mongooses, pheasants, feral cats, among other species who have found their way to these islands & caused various ecological upheavals, and she has helped me to appreciate them all. Still, seeing any of these species will never get me nearly as excited as spotting any of the remarkable endemic creatures that have somehow survived the ecological mash-up on these islands — especially our beloved Hylaeus bees.

Here is Aidan’s account of some of our recent adventures on Kauai:

” After our causal and picturesque introduction at Kilauea Lighthouse and Hanalei Bay, we decided to engage in a more serious endeavor: camping on the Na’Pali coastline. We simply wanted to spend a night somewhere along the beach, check out the dramatic views, and peek around for any bees that might have taken refuge there. After finding that every tourist in Kauai is encouraged to attempt at least the first part of the trail, we dropped off our two hitchhikers at the trailhead to find parking a mile away, and bummed our own ride back. Apart from an overall sensation of deep penetrating moisture for 14 hours, it was a beautiful experience. While the rain is always a culprit in keeping the bees in hiding, we later discovered that much of the coast had actually been cultivated by generations of farmers for much of it’s history. This long term presence of both humans and agricultural plants make it likely that not only are there no bees there, but they probably have not been abundant in that area for some time.

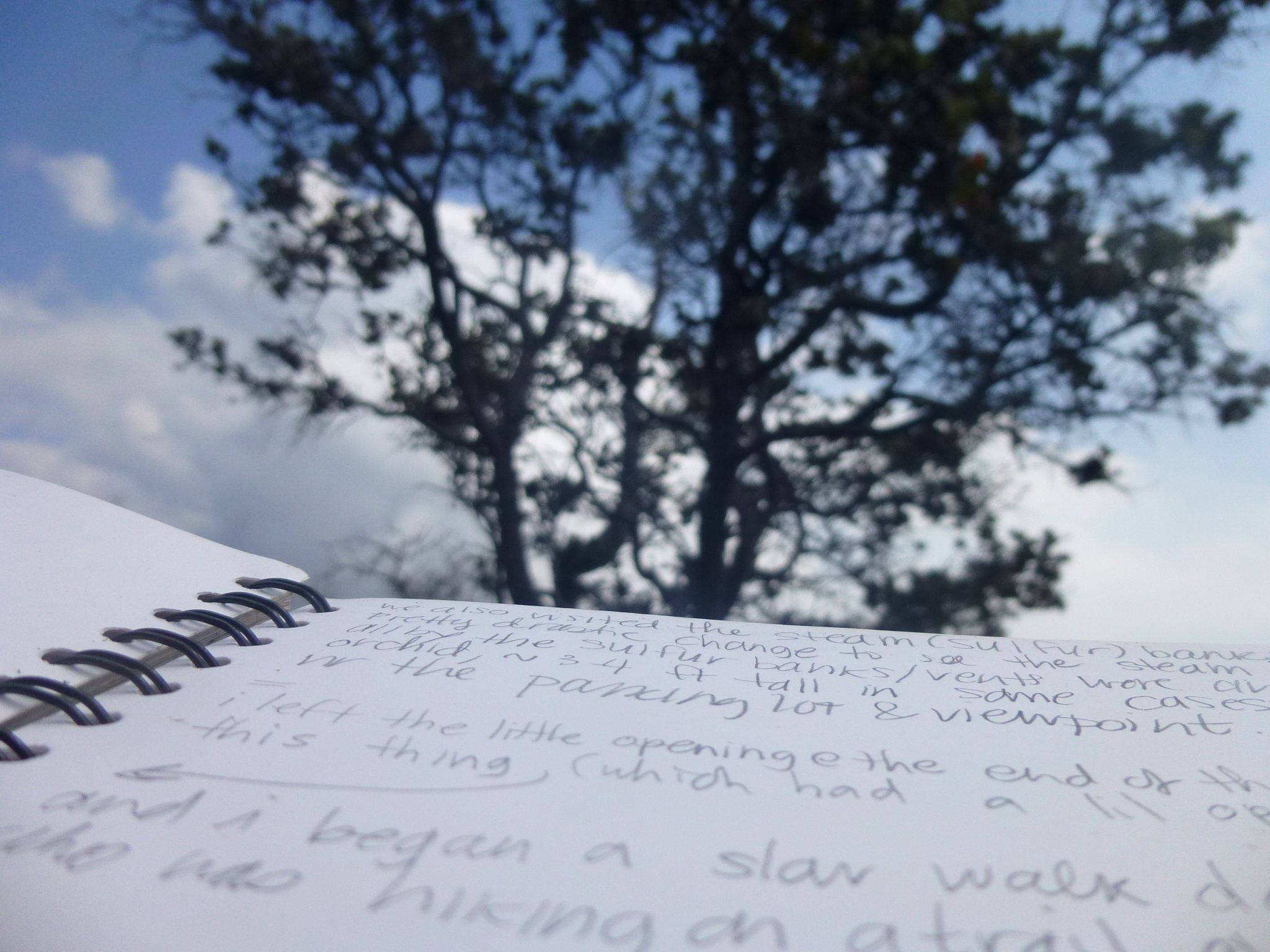

The second half of our week was used to explore the western side of the island, which in relative terms is just a few miles from where we were on the Na’Pali – but insurmountable canyons make it impossible to connect these via roadway. The Alakai Swamp proved to be one of the loveliest explorations of our entire trip (so far), and certainly a most pleasant hike. Nestled in the cloud tops, many of its spectacular views are rendered invisible by an opaque wall of white mist the majority of the day. The dominance of native plants was a big focus for us, as it’s altitude has prevented many invasives from penetrating the landscape. Massive tree ferns, uhule, and an overflowing forest of ohia were present for much of our hike. The end of the trail plateaus in deep wetlands giving way for an especially unusual sight: stunted, bush-like ohia growing amidst the mossy, wet, swamp floor. We found few in flower though, and intermittent rains reduced our likelihood of spotting bees. Luckily the variations in ecosystem and departure from the beach environment gave us constant stimulation. On our return we were treated to the most magnificent of views: a narrow sweeping valley cradled by startling blue canyon walls lying on the edge of the ocean. The water’s infinite presence spread up into the horizon making its transition indecipherable, the only clue as to separation being the long cast shadows of billowing clouds off the sparkling blue surface. As this view became distorted once again by mist, a vivid arc of a rainbow appeared directly behind us on the trail, leaping into the forests to the east.

We returned again to the coast the following day. Polihale is a beach park furthest west before hitting the Na Pali cliffs. We managed to pull our little corolla down five miles of sand, potholes and rocks to find an open, welcoming community and habitat. We were joined the first evening by our host Ashley and her boyfriend Sam. They graciously shared their food, fire, hammocks, and of course their lovely company, with us. The long expansive beaches, easy rolling waves, and good deal of plant life made this an ideal location for focusing in again on our bees. We quickly found out, we were also sharing this temporary home with a myriad of ant populations, wasps, cockroaches, roly-poly’s, mosquitos, and flies, many of whom we felt throughout the night. This was accompanied by the buzz of cicadas and roosters crows. There was plenty of naupaka, heliotrope, and even [some] false sandalwood also in the area. On one of these trees I was able to find myself a postmortem hylaeus sample, which makes business far easier than netting one flying frenetically about. I must mention also that our impressions there were polarized – one night we were privy to the distant splashes of dolphins in front of a setting sun, a mesmerizing and utterly beautiful experience. [On our final night at Polihale], our attention was drawn back to the water only to witness the rising black smoke of a naval frigate boat deploying test rounds into the waters. The booms echoed loudly from the canyon walls behind us in a startling and upsetting interference.

Our week in Kauai took us deeper into contemplation of the impacts of the army, GMOs, and invasives in this fragile island ecosystem, and we had a marvelous time. So much magic can happen in the smallest places, and definitely happened for us. Mahalo Kauai! “